Rents haven’t been outpacing property costs or people’s wages.

A simple comparison of rents vs. property ownership costs suggests that landlords are generally trying to keep the two aligned, but sometimes they have to accept minimal rental growth due to the underlying anchor of wage growth (i.e. what tenants can actually afford). This isn’t currently deterring them, with investors’ share of property purchases still reasonably strong.

CoreLogic research analyst Kelvin Davidson writes:

Residential property investors are clearly under the pump from the government at the moment, facing increased costs and regulatory pressures, including higher quality standards (e.g. insulation), increased tenant rights, and pending removal of negative gearing.

From an investors’ perspective, it’s entirely understandable that they might seek to recoup some of this through charging higher rents to tenants – especially in the current environment of low gross yields and reduced prospect of strong capital gains in the future. But can landlords actually push through rent increases? Will they even want to do so?

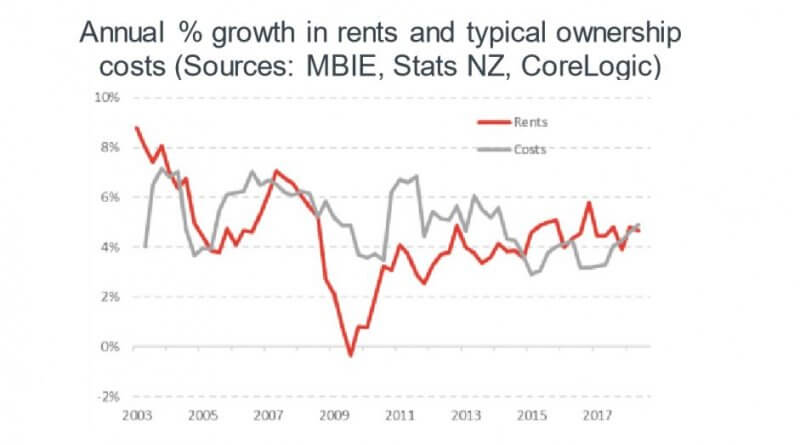

We’ve looked into the issue and constructed a basic measure of the costs of owning property, using components of the CPI*. It’s important to point out that this isn’t a comprehensive measure, just indicative. However, it does help to illustrate that landlords aren’t always profiteering at the expense of tenants – for example, costs rose faster than rents for a long period between 2008 and 2014 (see the first chart). Over the full period shown in the chart, property ownership cost growth has averaged 5.0%, only a little more than rental growth of 4.4%.

So while landlords will generally be trying to keep rents in line with their costs to maintain margins, sometimes they can’t. And as the second chart illustrates, a big factor here is the anchor of income growth. On average across a number of cycles, rental growth has tended to move in line with how quickly (or slowly) incomes are rising.

Moreover, the use of “generally” in the previous paragraph was a considered choice, because sometimes even if rents could be raised, landlords may not want to. If you have a reliable tenant, the risk that they move out can defeat the purpose of a rent rise in the first place – vacancies even for one or two weeks drastically affect profits, as do higher management/maintenance costs from a less reliable tenant. The combination of not always being willing or able to raise rents helps to explain why gross yields have fallen so far (third chart).

Thinking ahead, most commentators expect wage growth to pick up, but it’s unlikely to sky-rocket higher, so landlords may have to continue to plug away with small rent rises and low yields. But that seems unlikely to cause a mass exodus from the sector. Indeed, investors are still actively buying properties and anecdotally there aren’t many existing landlords looking to sell some or all of their properties. As the fourth chart shows, multiple property owners (MPOs) with a mortgage are showing signs of a return to the market, and MPO cash (those investors who don’t need a mortgage) are continuing their gentle upwards movement too.

View More HERE at CoreLogic

Kelvin Davidson Senior Research Analyst, 027 355 3813, [email protected]

Enquiries can also be directed to [email protected]

* These are: property maintenance materials & services, water supply, refuse disposal and recycling, local authority rates and payments, dwelling insurance.

CoreLogic